THE ROMANTIC POEM ‘DIALOGUE Between Fashion and Death’ is curious and resonating work that deals with the powerful connection between dress and mortality. The piece presents ‘Fashion’ as a fictional character in conversation with ‘Death’, that is, like Death, actively responsible for human suffering. Conceived by the Italian poet, essayist, and philosopher Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), it has since been adopted into the context of fashion discourse as a powerful rendering of fashion’s capacity to engage with our own transience.

Born and educated within the small, but deeply conservative and religious town of Recanati in Italy, Leopardi is best known for his substantial contribution to Romanticism during the first half of the nineteenth century. Characteristically pessimistic and dark, Leopardi’s work often negotiates societal morals and is underpinned by a constant fascination with life and death, and the fineness of the boundary between the two. Writer Adam Kirsch, in an article for The New Yorker, described him as ‘the supreme poet of passive, helpless suffering’.1 Throughout his own life Leopardi was plagued with ill-health, scoliosis and physical pain that arguably manifests in his writings. Despite this, his is distinguished as one of the most important figures of Modern discourse, particularly in Italy.

Leopardi originally wrote ‘Dialogo Della Moda E Della Morte’, (or ‘Dialogue Between Fashion and Death’) for the book Le Operette Morali (later translated to English as Essays and Dialogues), in 1824 when he was twenty-six years old. The book is an unusual publication in itself as it is a collection of ‘dialogues’ written almost as poems or short stories between various counterpoints, such as in ‘Dialogue between Physicist and Metaphysicist’ and ‘Dialogue between Hercules and Atlas’, each communicating a message, or moral lesson. Like many of the others, the conversation between Fashion and Death takes the form of a poetic dialogue. It begins with Fashion calling out to Death for recognition, claiming they are sisters: ‘Do you not remember we are both born of Decay?’ [2]. Death, with failing hearing and sight, does not recognise Fashion, who insists that they are bound by the fact that they ‘both equally profit by the incessant change and destruction of things here below’, that, ‘our common nature and custom is to incessantly renew the world.’2 Death and Fashion, as Leopardi proposes in the poem, are of the same breed, both the executing decay and destruction on the body. Leopardi’s rather bleak, and at times playful depiction of fashion and death as fictional characters, conceptualises Fashion. The poem is rendered particularly profound and lasting in the context of contemporary fashion, or moreover, contemporary fashion writing. The work resonates in this context as an unusual example of fashion literature that critiques and parodies, the frivolousness of fashion. Even as this is written before the beginning of the development of the fashion industry into the Modern system (post-Industrial Revolution, Post-Charles Worth) we know it as today, the sentiment remains powerful.

Leopardi’s expressive and bleak words ultimately render Fashion as a cruel and destructive character, a perpetrator of suffering to the body whose doing is to ‘pierce ears, lips, and noses, and cause them to be torn by the ornaments I suspend from them.’ Fashion ultimately proves to Death their sisterhood in describing these inflictions on the human body. Towards the end of the dialogue the pair, somewhat perversely, race, in a sort of test to each other. Throughout the dialogue Fashion persists that she is an advocate of Death, aiding in the endeavour of shortening human life, a bleak and fantastical proposal supported by examples of the corset, the contortion of bound feet, of scarification and tattooing and painful ornamentation that damages human health and the body.

Aesthetics and trends in fashion, more so than ever before, constantly toy with symbolism and representations of death and human frailty. Among many other examples, Alexander McQueen’s theatrical and visceral designs, to the startling realism of fashion photographer Corinne Day, or Mugler’s 2011 campaign with Rick Genest, AKA Zombie Boy. ‘Death’ it seems, moves in and out of fashion on a regular basis. Although it might be a stretch to say that fashion allows us to negotiate the limits of our own mortality and thus become more reconciled with death, there is certainly a powerful connection between the two realms that Leopardi adeptly captures in this work.

***

Dialogue Between Fashion and Death (1824) by Giacomo Leopardi, and translated by Charles Edwardes in 1857

Fashion: Madam Death, Madam Death!

Death: Wait until your time comes, and then I will appear without being called by you.

Fashion: Madam Death!

Death: Go to the devil. I will come when you least expect me.

Fashion: As if I were not immortal!

Death: Immortal? “Already has passed the thousandth year,” since the age of immortals ended.

Fashion: Madam is as much a Petrarchist as if she were an Italian poet of the fifteenth or eighteenth century.

Death: I like Petrarch because he composed my triumph, and because he refers so often to me. But I must be moving.

Fashion: Stay! For the love you bear to the seven cardinal sins, stop a moment and look at me.

Death: Well. I am looking.

Fashion: Do you not recognise me?

Death: You must know that I have bad sight, and am without spectacles. The English make none to suit me; and if they did, I should not know where to put them.

Fashion: I am Fashion, your sister.

Death: My sister?

Fashion: Yes. Do you not remember we are both born of Decay?

Death: As if I, who am the chief enemy of Memory, should recollect it!

Fashion: But I do. I know also that we both equally profit by the incessant change and destruction of things here below, although you do so in one way, and I in another.

Death: Unless you are speaking to yourself, or to some one inside your throat, raise your voice, and pronounce your words more distinctly. If you go mumbling between your teeth with that thin spider-voice of yours, I shall never understand you; because you ought to know that my hearing serves me no better than my sight.

Fashion: Although it be contrary to custom, for in France they do not speak to be heard, yet, since we are sisters, I will speak as you wish, for we can dispense with ceremony between ourselves. I say then that our common nature and custom is to incessantly renew the world. You attack the life of man, and overthrow all people and nations from beginning to end; whereas I content myself for the most part with influencing beards, head-dresses, costumes, furniture, houses, and the like. It is true, I do some things comparable to your supreme action. I pierce ears, lips, and noses, and cause them to be torn by the ornaments I suspend from them. I impress men’s skin with hot iron stamps, under the pretence of adornment. I compress the heads of children with tight bandages and other contrivances; and make it customary for all men of a country to have heads of the same shape, as in parts of America and Asia. I torture and cripple people with small shoes. I stifle women with stays so tight, that their eyes start from their heads; and I play a thousand similar pranks. I also frequently persuade and force men of refinement to bear daily numberless fatigues and discomforts, and often real sufferings; and some even die gloriously for love of me. I will say nothing of the headaches, colds, inflammations of all kinds, fevers – daily, tertian, and quartan – which men gain by their obedience to me. They are content to shiver with cold, or melt with heat, simply because it is my will that they cover their shoulders with wool, and their breasts with cotton. In fact, they do everything in my way, regardless of their own injury.

Death: In truth, I believe you are my sister; the testimony of a birth certificate could scarcely make me surer of it. But standing still paralyses me, so if you can, let us run; only you must not creep, because I go at a great pace. As we proceed you can tell me what you want. If you cannot keep up with me, on account of our relationship I promise when I die to bequeath you all my clothes and effects as a New Year’s gift.

Fashion: If we ran a race together, I hardly know which of us would win. For if you run, I gallop, and standing still, which paralyses you, is death to me. So let us run, and we will chat as we go along.

Death: So be it then. Since your mother was mine, you ought to serve me in some way, and assist me in my business.

Fashion: I have already done so — more than you imagine. Above all, I, who annul and transform other customs unceasingly, have nowhere changed the custom of death; for this reason it has prevailed from the beginning of the world until now.

Death: A great miracle forsooth, that you have never done what you could not do!

Fashion: Why cannot I do it? You show how ignorant you are of the power of Fashion.

Death: Well, well: time enough to talk of this when you introduce the custom of not dying. But at present, I want you, like a good sister, to aid me in rendering my task more easy and expeditious than it has hitherto been.

Fashion: I have already mentioned some of my labours which are a source of profit to you. But they are trifling in comparison with those of which I will now tell you. Little by little, and especially in modern times, I have brought into disuse and discredit those exertions and exercises which promote bodily health; and have substituted numberless others which enfeeble the body in a thousand ways, and shorten life. Besides, I have introduced customs and manners, which render existence a thing more dead than alive, whether regarded from a physical or mental point of view; so that this century may be aptly termed the century of death. And whereas formerly you had no other possessions except graves and vaults, where you sowed bones and dust, which are but a barren seed, now you have fine landed properties, and people who are a sort of freehold possession of yours as soon as they are born, though not then claimed by you. And more, you, who used formerly to be hated and vituperated, are in the present day, thanks to me, valued and lauded by all men of genius. Such an one prefers you to life itself, and holds you in such high esteem that he invokes you, and looks to you as his greatest hope. But this is not all. I perceived that men had some vague idea of an after-life, which they called immortality. They imagined they lived in the memory of their fellows, and this remembrance they sought after eagerly. Of course this was in reality mere fancy, since what could it matter to them when dead, that they lived in the minds of men? As well might they dread contamination in the grave! Yet, fearing lest this chimera might be prejudicial to you, in seeming to diminish your honour and reputation, I have abolished the fashion of seeking immortality, and its concession, even when merited. So that now, whoever dies may assure himself that he is dead altogether, and that every bit of him goes into the ground, just as a little fish is swallowed, bones and all. These important things my love for you has prompted me to effect. I have also succeeded in my endeavour to increase your power on earth. I am more than ever desirous of continuing this work. Indeed, my object in seeking you to-day was to make a proposal that for the future we should not separate, but jointly might scheme and execute for the furtherance of our respective designs.

Death: You speak reasonably, and I am willing to do as you propose.

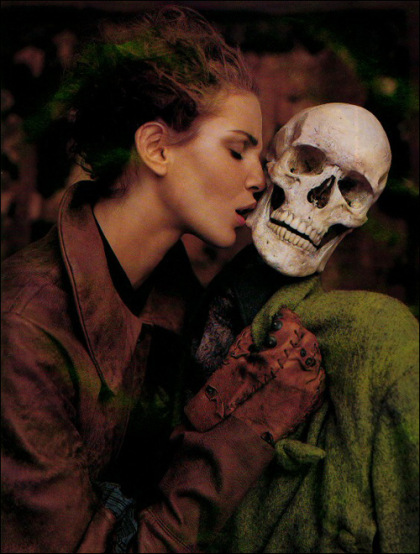

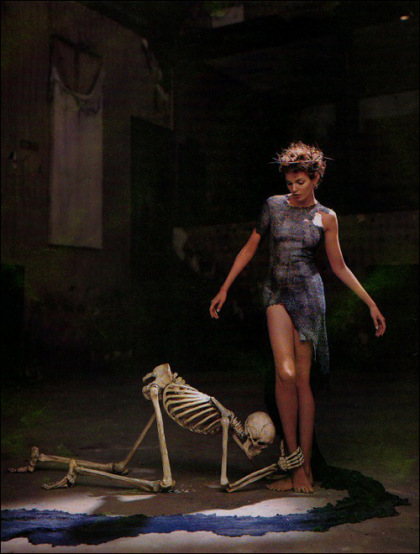

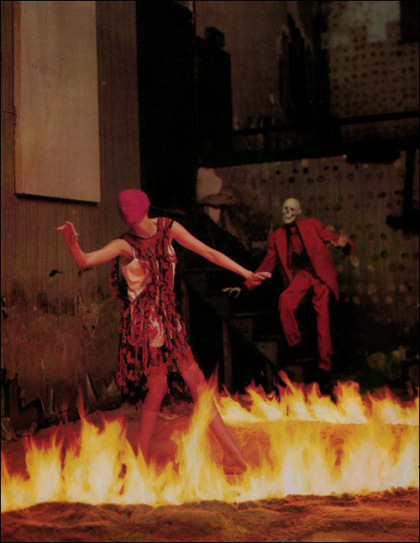

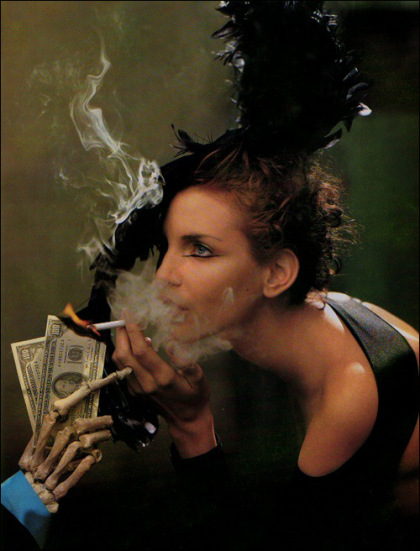

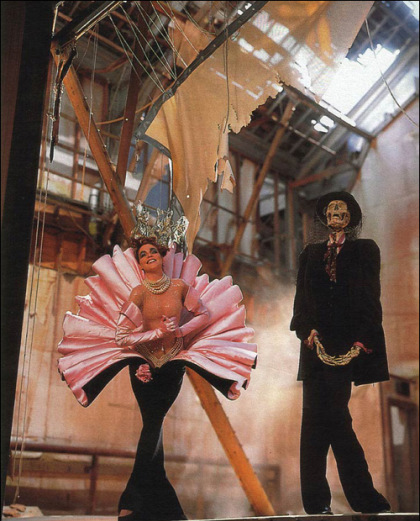

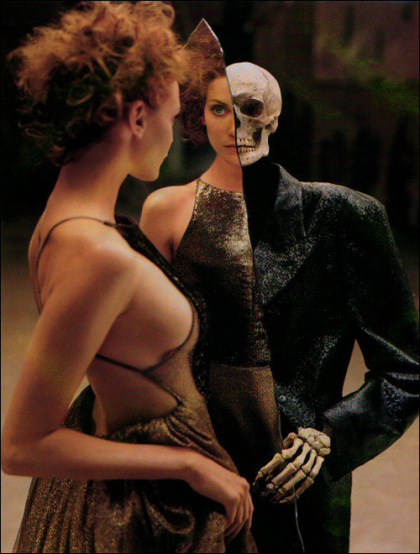

All images from the series ‘In Memory of the Late Mr. and Mrs. Comfort, a fable by Richard Avedon’ with model Nadja Auermann, commissioned in 1995 by The New Yorker.